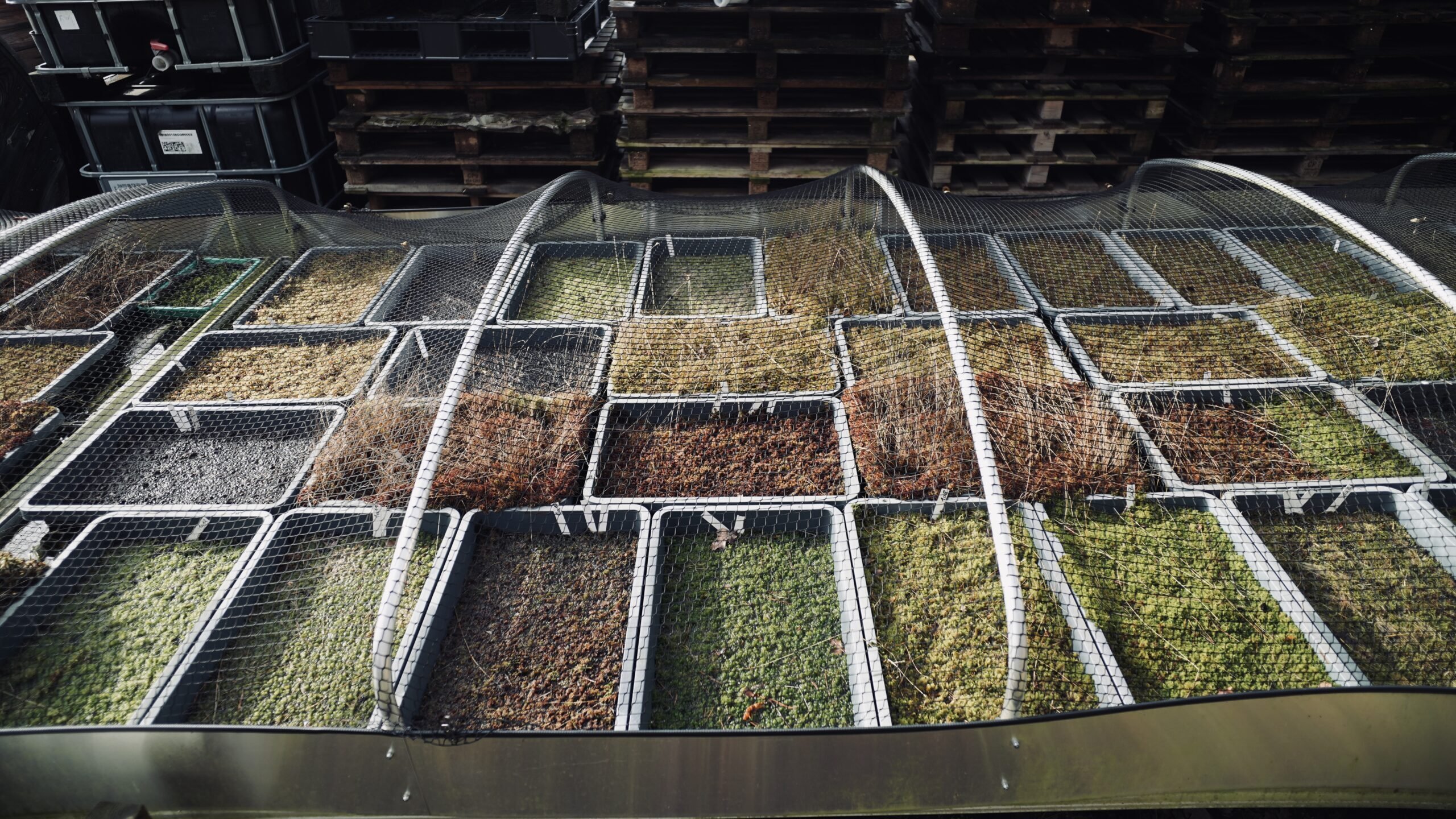

Last week Tuesday we visited the Totes Moor near Hanover. On bumpy moorland roads, we made our way to an important peatland area belonging to the Steinhuder Meer Ecological Protection Station (ÖSSM), whose renaturation we are supporting with our Mission to Marsh. We wanted to find out what the peat mosses there were up to. We met Corinna Roers, the project manager, with whom we first took a look at the long, impressive peat moss tables. The small miracle plants grow on the tables, which are essential for nature conservation in the raised bog, but are currently still very rare. Of course, we couldn’t pass up the opportunity to visit the area that is currently being renaturalized. With peat mosses in all kinds of shapes and colors, an orange-colored moor railway and lots of exciting specialist knowledge, we had a successful excursion to the Totes Moor.

You thought mosses always looked green and fluffy? Then that is definitely only half the truth. The peatland is home to all kinds of different mosses and other cool plants. From Sphagnum palustre (marsh peat moss) to Sphagnum cuspidatum (sphagnum peat moss), Rhynchospora alba (white beak reed) and Vaccinium oxycoccos (common cranberry), we have discovered a kind of scientific moss paradise. Rhynchospora alba, also known as beak reed, plays an important role in the renaturation of raised bogs despite its inconspicuous appearance. As a pioneer plant, along with cotton grasses, it is one of the first to recolonize peat soils after peat extraction and form dense areas where peat mosses can spread. In contrast to the beak reed, the peat moss Sphagnum cuspidatum spreads masterfully and efficiently. It uses every open gap to spread out and shimmers in a striking, light green color.

The chugging of the old moor railway

After marveling at the growth of the mosses on the cultivation tables, we wanted to get an idea of what the renaturation area looks like. To do this, we drove about 10 minutes by car to the project areas in the nature reserve. We had to walk along the moss-covered tracks of the old moor railroad on the muddy, dark moorland. At first glance, it gave the impression that the steady chugging of the moor railway was a thing of the past. Alex is still engrossed in taking photos when Anni suddenly calls out: “Alex, the moor train is coming!”. The driver stands casually leaning in front and greets us while the whole ground around us begins to vibrate. Definitely a small highlight! The moor train is still being used to transport peat, but as soon as the area can be extensively renaturalized or inoculated* with peat moss, the mosses will reclaim the area.

*Inoculation is the process by which peat mosses are applied to peat-covered areas to enable their reintroduction.

On the edge of ordinary perception

To the east of the moor railroad is a barren brown desert landscape. Peat has not been extracted here for a few years, but without renaturation measures it will no longer be possible to create a near-natural raised bog. The reason for this is that it is a moorland edge area where the soil has already dried out too much to be able to store water again. To the west of the tracks is the moorland area that was renaturalized four years ago. Dense, moist moss carpets up to 10 cm thick are now growing there. Shimmering green-reddish, the mosses look quite inconspicuous from a distance. Mosses only reveal their true beauty on closer inspection. But then, as author Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in her book “Collecting Moss”, these special plants allow us to “linger for a brief moment on the edge of ordinary perception”.

Mosses: Between life and death

The area is currently well soaked because it has rained a lot. A real blessing for peatland protection. However, too much moisture is also not good for the mosses. While they can survive drought for a long time, they can only survive waterlogging for a short time. Therefore, controlling the water level is crucial for the safe establishment of peat mosses. Corinna explains that a pump will soon be installed in the area so that the water can be transferred to or drained from the corresponding areas as required. Above the water surface and without access to water, dry peat mosses turn whitish. Then they look like tiny skeletons. In fact, this is where the name “pale moss” comes from. In this state, however, they are anything but dead, as peat mosses can reach a state between life and death. As soon as they come into contact with water again, they begin to photosynthesize again and regain their bright green color. So quickly back into the water with the little peat moss! How long do you think peat moss can survive in a dry state? The resolution will be available next week.

After the successful tour, we are still engrossed in conversation for a few minutes when Corinna hesitantly asks, “Are you going to find your own way out?”. She would like to carry out a few more tests on the trial area. Alex replies confidently: “Of course, we made it from the wetlands of Canada to Patagonia, we’ll manage.”